Squaring the Circle: How Pi (1998) Helped Me Articulate my Autism through Film

Georgia Kumari Bradburn, February 2025

When we talk about a film being “autistic”, what exactly do we mean by this? A film cannot be “diagnosed” with something, or assessed in the way that we assess human beings. Or can they?

I often struggle to align myself with the themes and aesthetics of films made by filmmakers with a clear neurotypical approach, but every so often there comes a film that resonates so strongly with my experience of the world that I am caught off guard. A film that articulates something so specifically tailored to my neurodivergence that I immediately go to look up if the filmmaker is autistic. More often than not, this is not specified, and indeed filmmakers have no obligation to explain their work or identity. It’s usually not the filmmaker that matters. It’s the choice of aesthetics, themes and characters that somehow presents a vision of reality that is an uncanny reflection of my own divergence from neurotypicality.

The discussion of autistic representation in the media has existed for many years, going round in circles about ethics, responsibility and authenticity - the Rain Man debate. This is not something that interests me, since most characters are fictional. What I am interested in is an autistic/neurodivergent truth communicated through cinema, through cinematography, editing, mise-en-scene, sound and performance. An atypical brain woven through the fabric of the film itself. A film that can stim, hyper-fixate, become overwhelmed, and experience meltdown.

This was my thesis going into creating my undergraduate short film, A Brief History of Circles - a film that simulates autistic thought and expression through sound, montage, and an intense fascination with circles. Just as artists of all mediums use their craft to express feeling, I have always felt an urge to express my differences through cinematic tools, to articulate pre-articulative sensations that cannot be expressed through words alone. I was inspired by films that contain audiovisual elements to which I felt a strong bodily connection to. After all, stimming and hypersensitivity are rooted in the body, so therefore on-screen translations of these sensations also must be inherently connected to the body. As philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty observes, “[the] body is the fabric into which all objects are woven” (Merleau-Ponty 1962).

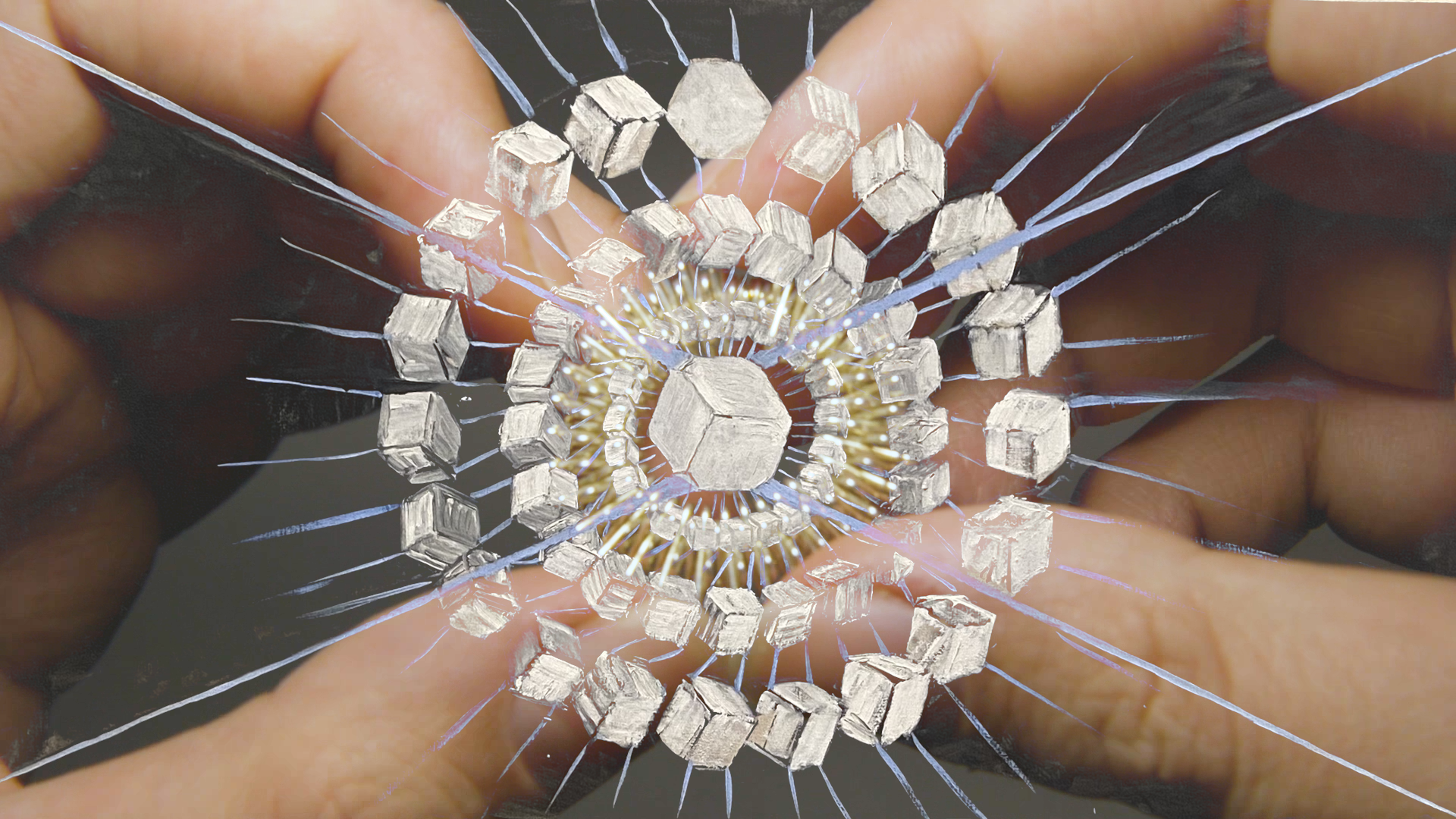

As we were putting together the programme for Stimema, our series of films reflecting neurodiverse perspectives at the BFI, I had a very clear idea of the feature that I wanted to screen alongside my short film. Darren Aronofsky’s debut feature Pi (1998) was one of the first films that I immediately identified as an “autistic” film, not just through character, but through its aesthetics and themes. The film follows Max Cohen, a genius mathematician who believes that everything in nature can be understood through numbers, seeking an underlying pattern that could explain the secrets of the universe. Despite the film itself not explicitly having anything to do with autism, it reached me in a very specific place of bodily resonance.

There is a reason why I chose circles as the object of obsession in my own film, directly inspired by the titular fascination in Pi. I have always relied upon the comfort of circular, or repetitive, motions - leg tapping, finger waving, rocking my body back and forth - to regulate energy, excitement, or discomfort. These movements are called “stims”, or “self-stimulating behaviours,” associated with neurodivergence but actually inherent within all human beings. As babies we are rocked to sleep, and that repetitive motion that stimulates our vestibular system becomes a constant, a coming-and-going that we can rely on to feel safe. The circle emulates this pattern; it begins and ends in the same place, it is a fact. From the outside, there is nothing explicitly speculative, unstable or inconsistent about the circle. Though I always struggled with maths at school, I liked Pi because it enabled the circle’s perfection: πd gives you the circumference, πr^2 gives you the area. π is an irrational number, it never ends. It is constant, and it is also an indisputable fact.

Perhaps this consistency is what seduces Max Cohen, who hypothesises that “mathematics is the language of nature,” citing Fibonacci, Pythagoras and da Vinci, figures who helped to identify mathematical patterns all around us. Using his expert knowledge, Max seeks to identify a pattern that will allow him to predict the stock market, using his computer Euclid, named after the “father of geometry” who first defined the properties of the circle.

For Max, mathematics promises stability. Numbers are facts. Numbers can be constant. People, and therefore the outside world, are not. So Max locks himself away in his drab, wire-draped apartment and resents communication or distraction. When unwanted noises or presences seep into his machine-like interiority, Max begins to crash, or perhaps “meltdown” - a term used within the autism community to describe an intense, uncontrollable response to an overwhelming situation. The sounds of sexual moaning next door send him into an attack of cluster headaches, intrusive conversations make his hands and body start to jitter. This is something that especially resonates with me as someone with severe misophonia - a condition that causes decreased tolerance to specific sounds. I often experience episodes of complete meltdown in response to small sounds that interrupt my sense of control over my environment: a fork clattering on the ground, a loud sniffle, a high-pitched laugh. It sends my brain and body into overdrive, a glitch in my internal matrix that renders me completely non-functional.

Consistency is paramount for many autistic people. In a world built for neurotypical wants and needs, we are forced to exist in spaces that are too loud, too bright, too intense, to communicate with people in riddles that we don’t understand, to be denied opportunities and civil rights based on our inability to assimilate with “normality”. Life itself is made up of inconsistencies, and we spend our lives finding ways to make sense of it. We search for indisputable facts that we can always rely on to explain why things are the way they are, a form of God for those who cannot be religious for lack of solid evidence.

Max’s encounter with Lenny Meyer, a Jewish man attempting to decode the numerological patterns within the Torah to uncover a message from God, is an interesting parallel. We all have our deities: for marginalised people, they may appear as the only solution in a punishing world. Many autistic people, including myself, find this solace in facts and information, which, unlike many common faiths, can be backed up with solid evidence. We can rely upon what we know to be true to guide us on the proverbial path to salvation. But is it really all that simple? As Max discovers, the most significant threat to his faith in numbers is humanity, the prospect of human error disturbing his calculations, his sacred form of worship, his hyper-fixation.

It is this aspect of hyper-fixation - a term used to describe the intense fascinations and obsessions with hyper-specific subjects that autistic people often exhibit - running throughout Pi that helped me to structure A Brief History of Circles. Pi has a building rhythm, a sense of pulsing anxiety running through its duration that aligns itself with Max’s increasing obsession. I wanted to use this idea of an adrenaline current running through the film to illustrate how hyper-fixations can quickly go from a curious fascination to an all-consuming obsession, to the point where the obsession itself becomes too overwhelming for the senses to handle, resulting in a total sensory and emotional breakdown.

In line with my thesis, which argues for the prioritisation of autistic interiority, Pi situates us firmly in Max’s interior world. The use of the revolutionary Snorricam technology, which mounts the camera on the actor’s body with the lens turned to face them, aligns us with Max’s physical body and emphasises the shakiness and instability of the exterior world. Clint Mansell’s breakbeat score utilises Amen Break samples, which, when visualised in waveform, meet the points of the golden ratio, a mathematical phenomenon that validates Max’s obsession with underlying patterns everywhere. The wires and cables that adorn his abode refer to his highly formularised, code-seeking brain. Yet there are sequences in which Max encounters his brain outside of his body, discovering it not to be a highly functioning computer, but a bleeding lump crawling with flies (or perhaps “bugs”). Max comes face to face with his imperfection, his infallibility, his inconsistency, driving him to push the limits of his brain even further and, in turn, causing more self-harm.

Perhaps the argument here is that Max’s insanity is self-inflicted, but from a neurodivergent/disability perspective, the opposite is true. Max’s “special ability” - a term often used to reframe neurodivergence in a positive, yet often patronising, light - attracts a Wall Street firm to take advantage of his stock market predictions to gain control over the market. He is valued only for his skill, his ability to contribute to a corrupt network of greed, and yet his condition renders him completely incompatible with this same system. This paradigm of disability/ability, where a character’s ability renders them disabled without proper accommodations and support, is prevalent in many films, especially in the superhero genre.

Using autistic scholar Nick Walker’s definition of the progressive social model of disability, in which she states that “society isn’t set up to enable [one’s] participation,” without guaranteed long-term accommodations, we can say that Max is canonically, and by definition, disabled - or perhaps the opposite of enabled (Walker 2021). Max takes medication for his “attacks”, but they do not sustain him for long - a reflection of private healthcare systems that rely upon short-term solutions to ensure dependency. His disability renders him a victim of the hostile and exploitative capitalist system, the same way in which many autistic people with complex needs are left without proper access support in a world that is not built to accommodate them. My own arduous battle of applying for disability benefits and being turned down several times is an example of this, another aspect of my subjective experience of disability that aligns closely with Aronofsky’s protagonist, though he may not have intended for the character to resonate in such a way.

It is clear that the autistic experience can be located in Pi without the film itself having anything to do with autism. But is there really any value in finding autistic motifs in films that are not intended to be reflections of autism? It could be argued that these readings could, instead, perpetuate harmful stereotypes and further confine the definition of autism to a smaller criteria, the criteria that we see on screen. To suggest that Pi is an autistic film based solely on the fact that Max’s brain is comparable to a highly functioning computer would be an example of autism being reduced to a stereotype, that autistic people are all geniuses with robotic minds and a reduced capacity for emotion. I don’t consider myself to be a genius - if you dropped a box of matchsticks on the floor, I definitely would not be able to know instantly how many there were. I am not good at maths, and I consider myself to be highly sensitive to the emotions of others, but I am still autistic.

Autistic representation is not one-size-fits-all. The term “spectrum” is overused - I mostly see it used when people argue that one cannot be diagnosed as autistic because “we’re all somewhere on the spectrum”, a phrase that flippantly undermines real issues of ableism and discrimination that actually autistic people face daily. But it can apply to the conversation of representation - a spectrum of representation that helps us to avoid generalisation. An autistic cinematic language cannot be defined by a rigid diagnostic criteria, but can provide reflections of non-neuronormativity that may or may not resonate with an individual neurodivergent spectator. In the case of A Brief History of Circles, I intended to propose the possibility of autistic cinematic languages - plural. A spectrum of expressivity, reconfiguring and neuro-diversifying film language as we know it.

A Brief History of Circles is a cinematic reconstruction of my pre-articulative brain. A voiceover describes the history and mathematics of the circle, gradually beginning to glitch and loop, turning itself into a repetitive, “stimmy” rhythm. The circles in the montage begin to dissolve into one another, eventually building to an overwhelming climax of information, with the looping voiceover snippets attempting to provide a sense of stability. The film itself hyper-fixates on its own subject, leading to a meltdown caused by its own sense of unbalance.

As an artist, I can communicate what I don’t have words for, I can channel my interiority into an external work to achieve a sense of catharsis, of a burden of knowledge being released. For many neurodivergent artists and filmmakers who desire to channel their non-neuronormativity into their work, I think that it is positive to be able to identify traits, motifs and essences in existing films that lead us to define ourselves through cinematic tools. Pi’s restless, anxious search for patterns and answers, through the characters of Max Cohen, Lenny Meyer and even Marcy Dawson, the agent who stalks Max to extract his stock market predictions, can be a cathartic reference for neurodivergent filmmakers, like myself, in articulating our struggle to make sense of the baffling neurotypical world. Interpretations are subjective, but they can provide the foundations for new forms of cinema that allow marginalized groups to articulate themselves. They can enable neurodivergent filmmakers to reinvent cinema as we know it to include neurodiverse perspectives.

So does this mean that a film can be autistic? To analyse a film for its “autisticness” is not to uncover objective failures, to pathologize the film, but to explore the complexity and diversity of its meaning. I would argue that to identify films as autistic in fact subtly discourages the pathology paradigm, which views neurodivergence as something to be corrected, and instead embraces the neurodiversity paradigm, which champions an alternative way of existing in the world. Pi’s “autisticness” lies in its formal sensibilities and its central character who struggles to live on his own terms, to exist in an alternative way. It can reveal our own frustrations with the neurotypical world, validating our divergence from what is “normal”. It proposes a divergent frame of mind, within a divergent audiovisual format, that can inspire divergent filmmakers to reconstruct their own minds for the world to finally understand.

Pi is screening alongside A Brief History of Circles at the BFI Southbank on Monday 24th of February as part of Stimema: The Neurodiverse World on Screen, curated by Stims Collective.

References:

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception, trans. Colin Smith. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Walker, N. (2021). Neuroqueer Heresies: Notes on the Neurodiversity Paradigm, Autistic Empowerment, and Postnormal Possibilities. Fort Worth: Autonomous Press.

A Brief History of Circles (2024)

Pi (1998)

Sean Gullette as Max Cohen in Pi (1998)